“How aggressive is Aramaic aggressive magic?”: a paper by Chaja‑Vered Dürrschnabel

February 3, 2021, Chaya-Vered Dürrschnabel (Researcher, University of Bern) presented her paper “How aggressive is aggressive magic? Apotropaic aspects of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic curse bowl texts” at the seminar “Traditions of Magic in the Near East and Caucasus” (moderator: Alexey Lyavdansky, Senior Lecturer, IOCS HSE).

From the very beginnings of human culture, people have felt the need to protect themselves against malevolent supernatural entities. Archaeologists have discovered talismans, amulets, and other inscribed and un‑inscribed objects, dating even to the earliest human settlements, that were produced in order to keep malevolent entities such as demons away. These objects were either worn directly on the body or placed in strategically important places within the domestic environment, e.g. under the threshold or in the corners of the house, so that evil entities could not enter the domestic sphere.

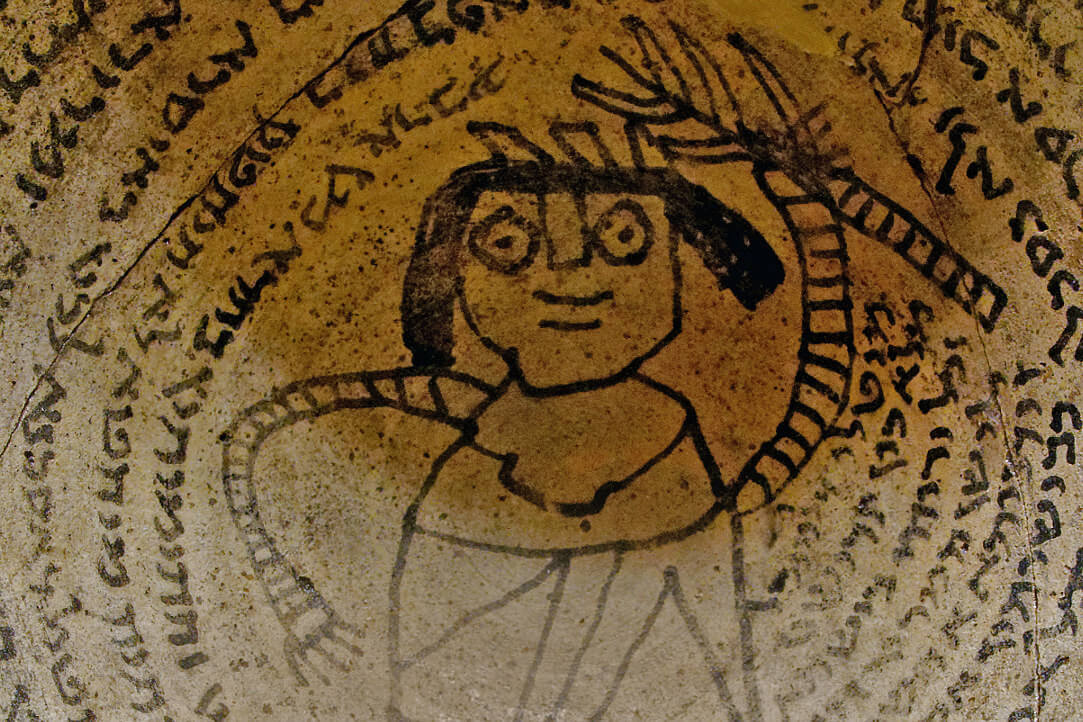

Many different kinds of amulets are known from Late Antiquity. Whereas in Asia Minor, Syria, and Palestine, lamellae, small inscribed metal plates normally rolled or folded and carried in containers around the neck, were predominant, there was a own tradition of apotropaic artifacts in Babylonia between the fourth and eighth century: incantation bowls.

Chaya‑Vered Dürrschnabel is a specialist in Hebraistics and Classical philology from Switzerland. Graduated from the University of Zurich (MA, BA) with a degree in Hebrew, Latin and Greek Philology, she has participated in international conferences, including the Colloquia in memory of I.M. Tronsky (St. Petersburg) and international conferences on Jewish studies, organized by the Sefer Center (Moscow). The defense of the doctoral dissertation of Ch.‑V. Dürrschnabel “The Language of the Curse: Aggressive Jewish Magic in Late Antiquty” is about to happen in the coming weeks at the University of Bern. During this year, her post‑doctoral project “Between Translation and translatio: On the Multilingual, Intercultural and Interreligious Nature of Late Antique Jewish Magic” will start at the Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies, HSE University. This project will be carried out under the supervision of Chief Researcher of IOCS Professor Nina Braginskaya. The project is funded by The Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe.

Nina Braginskaya

Professor

Alexey Lyavdansky

Moderator of the Seminar